All about solar eclipse

Eclipse \i klips′\ (n): the total or partial obscuring of one heavenly body by another.

There’s nothing wrong with the above definition of an eclipse, but it doesn’t begin to convey the thrill and excitement that takes hold of eclipse chasers when the Moon encroaches upon the Sun.

What’s more, a total solar eclipse is a rare event, cosmically speaking. There are close to 200 confirmed moons orbiting six major planets in our solar system (Mercury and Venus lack moons). But in only one instance is there a moon that’s the right size, and at the right distance from its planet, to just barely cover the brilliant solar disk and reveal the Sun’s wispy corona. And that’s our Moon. (Looked at another way, total solar eclipses aren't rare; they occur roughly once every year or two somewhere on Earth. But any given spot on our planet's surface gets darkened by the Moon's shadow on average only once about every 400 years, so in that sense totality is indeed rare.)

Cosmic Coincidence

The Sun’s diameter is about 400 times that of the Moon. The Sun is also (on average) about 400 times farther away. As a result, the two bodies appear almost exactly the same angular size in the sky — about ½°, roughly half the width of your pinky finger seen at arm's length. This truly remarkable coincidence is what gives us total solar eclipses. If the Moon were slightly smaller or orbited a little farther away from Earth, it would never completely cover the solar disk. If the Moon were a little larger or orbited a bit closer to Earth, it would block much of the solar corona during totality, and eclipses wouldn’t be nearly as spectacular.

Of course the Moon doesn’t totally eclipse the Sun every month — if it did, seeing totality wouldn’t be as much of a thrill. And even when the lunar disk encroaches on the Sun, it doesn’t always completely cover the solar disk. In fact, at new Moon — the only lunar phase when a solar eclipse can occur — the Moon usually misses the Sun altogether. Given all the variables, it’s almost surprising that we see eclipses at all.

A Celestial Dance

The Moon orbits Earth; both swing around the Sun. In a perfect universe, we’d see totality every month. But we don’t, and here’s why.

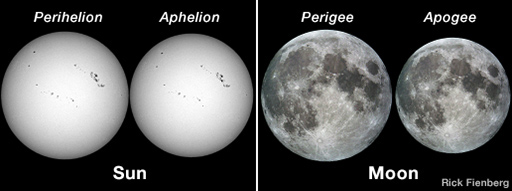

First, the apparent size of the Sun varies during the year because Earth’s orbit is an ellipse, not a perfect circle. Our planet is closest to the Sun (perihelion) in early January and farthest (aphelion) in early July. So the Sun appears about 3% larger in January than in July (not that you’d notice), which means at times it’s harder for the Moon to completely cover the Sun and create a total eclipse.

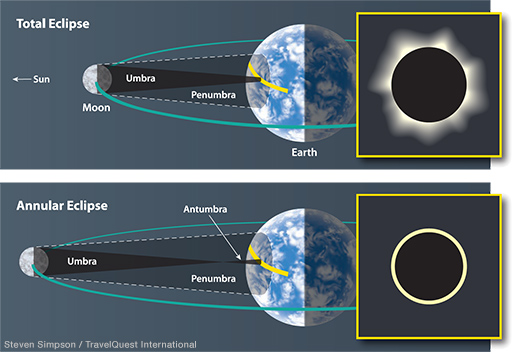

More dramatic is the change in the Moon’s apparent diameter due to its elliptical orbit around Earth. When the Moon is closest to Earth (perigee), its apparent diameter is 14% larger than when it’s farthest (apogee). When near perigee, the Moon can easily cover the entire solar disk and create a total solar eclipse. But at apogee the Moon is too small to cover all of the Sun's brilliant face. At mideclipse an annulus (ring) of sunlight surrounds the lunar silhouette, resulting in an annular eclipse.

The variability in the apparent size of the Sun and Moon doesn’t preclude a monthly solar eclipse. What does is the tilt of the Moon’s orbit, which is about 5° to the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun or, equivalently, the Sun’s apparent path around the sky as seen from Earth. (This path is called the ecliptic, for reasons that will become obvious in a moment.) More often than not, the new Moon passes above or below the Sun, and the lunar shadow misses Earth completely.

But every 173.3 days (roughly every 6 months), the new Moon passes through one of two crossover points (nodes) where the Moon’s tilted orbit intersects the ecliptic. Here, at last, a solar eclipse is possible, though the Moon can pass through a node without the eclipse being total or annular — a partial eclipse can occur instead.

Does this limit eclipses to twice a year? Not quite, because the Moon doesn’t have to move exactly through the middle of a node to cause an eclipse. It can be off by a little, which means it’s possible to have two solar eclipses within a month of each other, though both will be partials.

The complications don’t end there. The nodes slowly shift (precess) westward, which means the months in which eclipses take place slowly change as the years pass. This also affects the type of eclipse that occurs: currently long annulars are more likely in January, long totals in July.

Finally, after 6,585.32 days (18 years, 11 days, 8 hours), the entire eclipse cycle repeats. This is known as the Saros cycle. When two eclipses are separated by a period of one Saros, the Sun, Earth, and Moon return to approximately the same relative geometry, and a nearly identical eclipse will occur (though the eclipse path will be shifted west by eight hours — one third of Earth’s rotation).

Nothing Lasts Forever

The cosmic coincidence that gives us total solar eclipses isn’t permanent. The Moon is ever so slowly moving away from our planet at rate of about 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) per year. As it recedes, its average apparent diameter shrinks. Eventually, the Moon will never be large enough to completely cover the Sun, and total eclipses will no longer be visible from Earth’s surface.

And when might this sad prospect come to pass? The calculation is not precise — there are many unknowns such as whether the lunar retreat will continue at a constant rate and whether the solar diameter will remain stable over a long period of time. Still, about a billion years from now, give or take a few hundred million years, the surface of Earth will experience its final total eclipse of the Sun. Annular eclipses will continue to occur, though the percentage of the solar surface hidden by the Moon will gradually decrease.

So, when you stand in the lunar shadow watching the Moon pass between Earth and the Sun, revel in the knowledge that you are witnessing one of the most unusual and spectacular events in the cosmos.

0 Comments